A high-risk scientific mission to probe the ocean beneath Antarctica’s most unstable glacier collapsed just short of success after instruments became trapped deep inside the ice. The international effort, led by researchers from the British Antarctic Survey and South Korea’s polar programme, spent days drilling a narrow borehole more than 3,300 feet through the fast-moving main trunk of Thwaites Glacier, often referred to as the “doomsday glacier” because of its potential to dramatically raise global sea levels. Although the team collected rare, first-of-their-kind measurements from the seawater below, their attempt to install long-term monitoring equipment failed at the final stage, forcing them to abandon the instruments and evacuate the site.

Antarctica’s doomsday glacier in a race against time

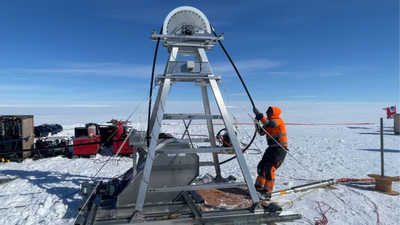

Working in one of the most hostile environments on Earth, the team of British and South Korean scientists used hot-water drilling to melt a one-foot-wide hole through nearly half a mile of ice. Once drilling began, time became the mission’s most precious resource. The borehole would start refreezing within about 48 hours unless kept open with continuous hot water. Strong winds delayed the start, while crevasses and shifting ice complicated operations. “You get your window of opportunity. You don’t have forever,” said Keith Makinson, a drilling engineer with the British Antarctic Survey.Before the failure, the team succeeded in lowering temporary instruments through the borehole and into the ocean cavity beneath the glacier’s main trunk. The measurements revealed turbulent seawater with temperatures high enough to drive rapid melting from below. “There’s plenty of heat to drive melting,” said Peter Davis, as data streamed in from beneath the ice. For scientists, these were the first direct observations from this critical part of Thwaites, long suspected to be a key weak point in the glacier’s stability.

Where the final step went wrong

The mission unravelled when researchers attempted to install a heavier, long-term mooring designed to transmit data by satellite for up to two years. As the cable was lowered, part of the equipment became stuck about three-quarters of the way down the borehole. The team believes refreezing ice or subtle shifts in the glacier narrowed the shaft just enough to trap a bulky chain at the bottom, causing the rest of the instruments to jam above it. “Realistically, whatever’s stuck there is frozen,” Makinson told colleagues as the team assessed their options.

Why scientists say the mission still matters

Despite the loss of the long-term instruments, the researchers say the expedition was not a failure in scientific terms. “This is not the end,” said Won Sang Lee, the expedition’s chief scientist from South Korea. The preliminary data confirmed that warm, dynamic ocean waters are actively eroding Thwaites from below, reinforcing fears that further retreat could destabilise much of West Antarctica. The team plans to return, arguing that the brief glimpse beneath the glacier proved both how dangerous Thwaites is and how vital it is to keep trying to understand it.